Global Sales Tax Compliance and Remittance

What I’ve learned over the last 18 months about when to use a third party merchant of record versus when to act as your own

For the last 18 months or so we’ve been wrestling with easily the most difficult product decision we’ve had to make in the six years since we started Outseta—how to handle global sales tax compliance.

Not only is this an issue for our own SaaS business, but we need to productize a solution that can be used by our customers, too.

Admittedly, our approach to date has been largely defined by a single word—inaction. That’s a reflection of the reality we’ve found—there are no great solutions to this problem available at the moment. And as you read on, I think you’ll come to a logical conclusion—how could there be?

Make no mistake about it—we’ve looked at just about every merchant of record and tax software vendor on the market today. We’ve talked to countless founders from companies of all stages and geographies. This post will share what we’ve learned about this topic.

Importantly, some of my original thinking on this topic has shifted based on what I’ve learned. I’ve flip-flopped on what the best approach to solving this problem is for our customers multiple times. But after all the time and energy I’ve spent exploring global sales tax compliance, I have finally developed some conviction on what represents the best approach given your circumstances.

As I share that thinking in this post, I’m making every attempt to balance sound legal guidance with the practical advice that I’d follow myself based on what I’ve learned.

Let’s start with the appropriate definition so we’re all on the same page.

What’s a Merchant of Record?

A merchant of record (MoR) is the entity that is authorized, and held liable, by a financial institution to process a consumer’s credit and debit card transactions. The MoR is also the name that appears on the consumer’s credit card statement.

In short, that’s just a fancy way of saying a merchant of record is who you are actually transacting with when you buy a product or service.

Most SaaS businesses today operate as their own merchant of record—Outseta included. We have our own Stripe account, and our customers purchase our products directly from us. Our company name appears on their bank statements. Importantly, this means that we have to calculate and remit global sales tax ourselves.

In short, that process is an administrative burden—particularly on small companies. That’s led, quite recently, to growth in the popularity of payment processors that act as a merchant of record on behalf of your business. Companies like Paddle, Gumroad, and Lemon Squeezy have grown in popularity largely because they act as the merchant of record for your business—they calculate and remit taxes for you, then issue your business a payout for the remainder of the revenue they’ve collected. The name of their company also appears on your customers’ bank statements.

There are pros and cons to being your own merchant of record, just as there are advantages to having someone else act as the MoR for you.

[fs-toc-omit]Disclaimer

Before we go any further—I am not a tax accountant and this is not legal advice. Neither myself nor Outseta is liable for any action or inaction that you take as a result of reading this article.

You’re responsible for your own business—which is ultimately one of the key themes in this article.

With that said, I do want to level. The reality of what’s happening in the real world with real businesses and the requirements around global sales tax remittance are completely unaligned at the moment.

At the end of the day I’m just a SaaS founder who has to wrestle with this problem myself—but because I need to productize a solution for our customers as well, I’ve researched this problem to death.

I’m 100% positive that I still don’t have it all right—this article and everything you’ll read on this topic will likely be met with strong opinions from all sides. I think I bring some credibility to this discussion for a simple reason—I’m one of the few people discussing this topic that's not trying to sell you something! Outseta does not offer a great solution to this problem at the moment—and our strategy is almost certainly going to be offering our customers both options.

There is way too much nuance in this discussion to call being your own merchant of record or working with a third party merchant of record a clearly better option—it completely depends on your business and circumstances.

What you need to start—and what you need to and scale

If you’re new to this topic, Justin Jackson and Jon Buda of Transistor.fm recently published three excellent podcast episodes where they share their journey wrestling with global sales tax compliance and remittance. These guys have been in the trenches battling with this topic—I’d highly recommend listening in to their experiences.

- Nobody in SaaS Wants To Talk About This

- Super Fun Sales Tax (Part Deux)

- This would kill our company immediately

You can just hear the frustration in their voices as they express the sentiment “We’re just trying to do the right thing.” But what’s most compelling to me is Justin’s sentiment around how ridiculous this all is.

Calculating and remitting global sales tax has nothing to do with paying taxes that your business owes. Instead, you’re being asked to calculate and remit sales tax to governments all over the world who simply haven’t figured out how to collect tax themselves! They’re putting it on you, the small business owner, to calculate and collect taxes for them. —Justin Jackson, Co-founder Transistor.fm

As we weigh the pros and cons of both options there are two lenses that I’ll return to because they are particularly important as we consider this topic.

- What you need to do if you’re just starting a SaaS business

- What you need to consider as you scale a SaaS business

I’ll return to both of these topics after we review the pros and cons of each approach.

Pros and Cons of Using A Merchant of Record

Pros

Convenience

I think the single biggest reason to use a merchant of record is simple—convenience. You don’t need to worry about calculating or remitting any sales tax because someone else is doing it for you. The administrative burden of that work is taken off your plate.

Cons

Slower approval processes

If you use a merchant of record, they need to carefully review who you are and what products you’ll be selling because they are legally responsible for all of the products and services sold on their platform. This typically results in slower approval times when you are just getting started as opposed to if you open your own Stripe account. It’s also common that businesses are rejected outright, without much indication as to why.

In my opinion, this is not a huge deal—if you’re starting a new business waiting a short period of time to get approved (assuming you will) shouldn’t be much of a barrier.

Customer Confusion

If you use a merchant of record, another company’s name is going to appear on your customers’ bank statements. They most likely expect that they’re paying your business, so when they see the name of the merchant of record on their statements it can be a little disconcerting.

I also don’t think this is too big of a deal. If you’re just looking at your bank statement, yes this can be a little confusing—but it’s easy enough to sort out.

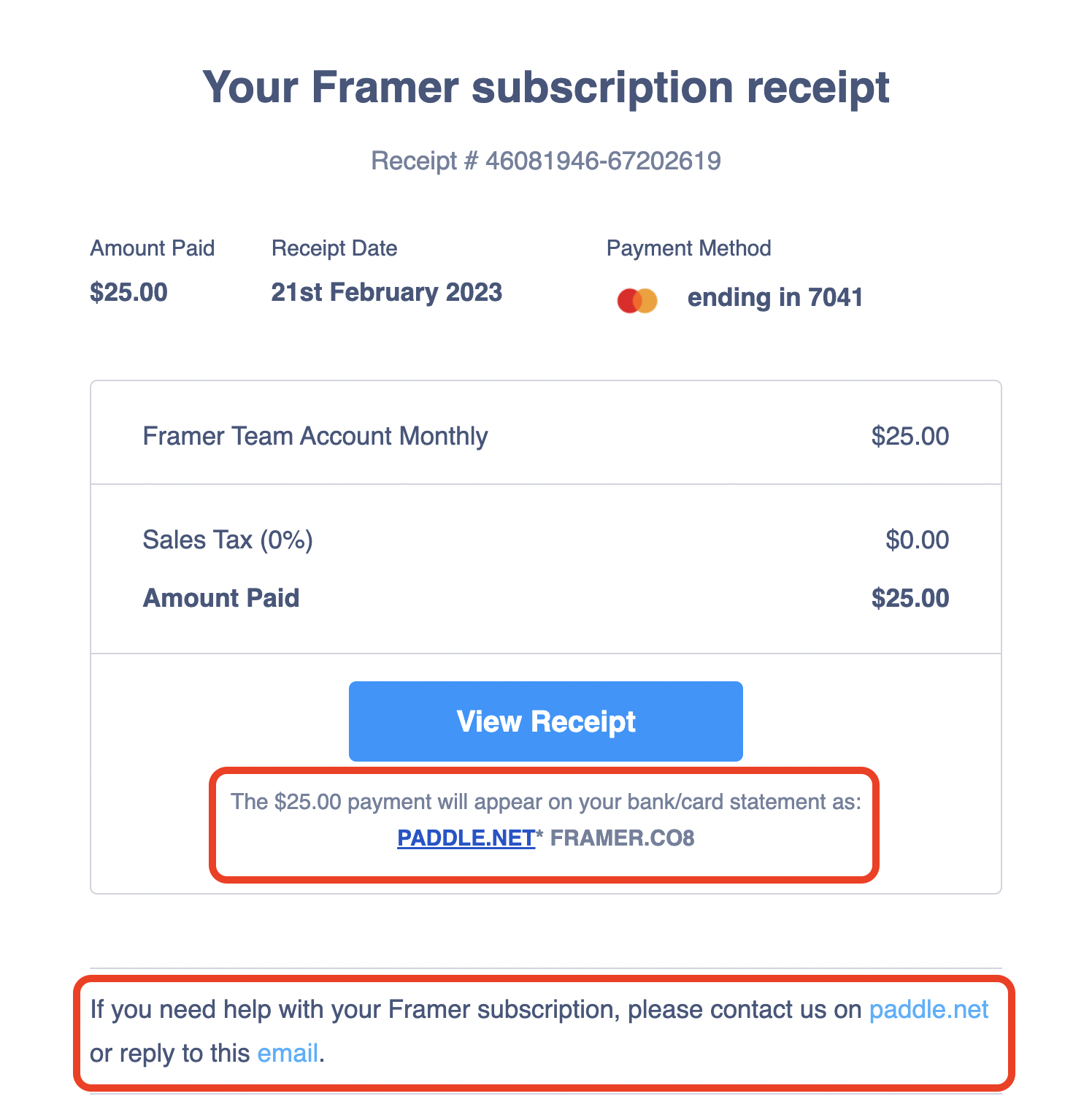

Here’s an example of an invoice from a company (Framer) that uses Paddle. Note that this is not a bank statement, but you can see how they try to address the issue. Notably, the email comes from help@paddle.com rather than from Framer.

Significantly greater platform risk

When you sell through a merchant of record, you take on substantially more platform risk—suddenly you’re not fully responsible for your own business; someone else is.

Put simply, the merchant of record is responsible for every product and service sold via their platform. If their approval processes don’t catch something—or if there’s a single bad actor within their customer base—all of the sellers on the platform are at risk.

Your business can be shut down for actions that had absolutely nothing to do with you.

Here’s Daniel Vassallo, the former Head of Product at Gumroad, speaking to that challenge.

A recent example of this concern, realized, happened with FlurlyApp—a marketplace that acted as a merchant of record for sellers on their platform. Due to a single seller’s bad behavior, the platform was shut down and fined $425,000 by Stripe. Here’s the letter from their CEO explaining what happened:

Flurly has been shut down by Stripe

Here’s what this meant for customers that relied on Flurly as a merchant of record.

As of this writing, no resolution has been found. The point is simple—it’s a very real possibility that your business could be on the receiving end of a similar email and could be penalized for something that had absolutely nothing to do with your business. Daniel Vassallo chiming in again in response to the Flurly fiasco:

I’m of the belief that the larger merchant of record platforms will encounter these issues enough that they’ll figure out a way through them—I suspect there are risk mitigation strategies, at least to some extent. But it's certainly not something the Merchant of Record has full control over my any means—they are at the mercy the compliance teams that make these decisions. I’s very difficult to say what the impact on your business would be or for how long—enough so that I view this as a really significant risk.

“That would kill our business immediately,” says Jon Buda, Justin’s Co-founder at Transistor.fm.

This risk does not only pertain to sellers using merchant of record platforms, but also poses risk to the merchant of record platforms themselves. The team at Revin recently shut down their own merchant of record business, pivoting to sell consulting services where they help companies calculate and remit global sales tax. The letter they sent to their own customers is telling.

The most relevant reason that we’re shutting down is the merchant of record model is too risky for both sellers and the merchant of record operator. Sellers bare the risk of platform shutdown as seen in the example of Flurly and Stripe. Furthermore, it became increasingly clear that the merchant of record model primarily appeals to small scale sellers or businesses with questionable or high risk business models. The recent changes in Stripe’s risk behavior has caused us to experience issues with keeping Stripe accounts live.

In short, every single customer on a merchant of record platform exposes you to risk—and you have no idea who those customers even are. I know people will push back on this concern, but I have a really straightforward perspective on this.

There are real world horror stories of businesses being shut down because they used a MoR. No one I talked to for this article had ever heard of a single instance where a foreign government went after a small SaaS company for any issue related to global sales tax compliance. Not one.

The more that I learned about this topic, the more this concern grew—it’s one of the primary reasons I would look to not use a merchant of record and instead keep the fate of my business in my own hands, based on my own decisions and actions.

Higher payment processing fees

I don’t know how to say this more clearly—you will end up paying more in payment processing fees with a merchant of record. As you should—you’re paying for the convenience of someone calculating and remitting your taxes for you!

What is absolutely correct is that using a merchant of record can result in similar payment processing fees if compared to a company that’s acting as their own merchant of record if they've elected to use 3-4 additional Stripe products. But most companies that choose to act as their own merchant or record do so with mitigating payment processing fees in mind, resulting in them paying lower fees.

As of this writing:

- Paddle and Lemon Squeezy charges a 5% fee + $.50 per transaction

- Gumroad charges a flat 10% fee, plus Stripe fees (12.9% total for US based businesses)

But if you look more closely, there’s often fine print. For example, if you sell a software subscription to an international customer the 5% fee immediately goes up to 7%. It's worth note that this occurs with Stripe's processing fees too, but they are lower to start with. These higher fees will affect every recurring transaction forever, so these higher fees only become more significant over time.

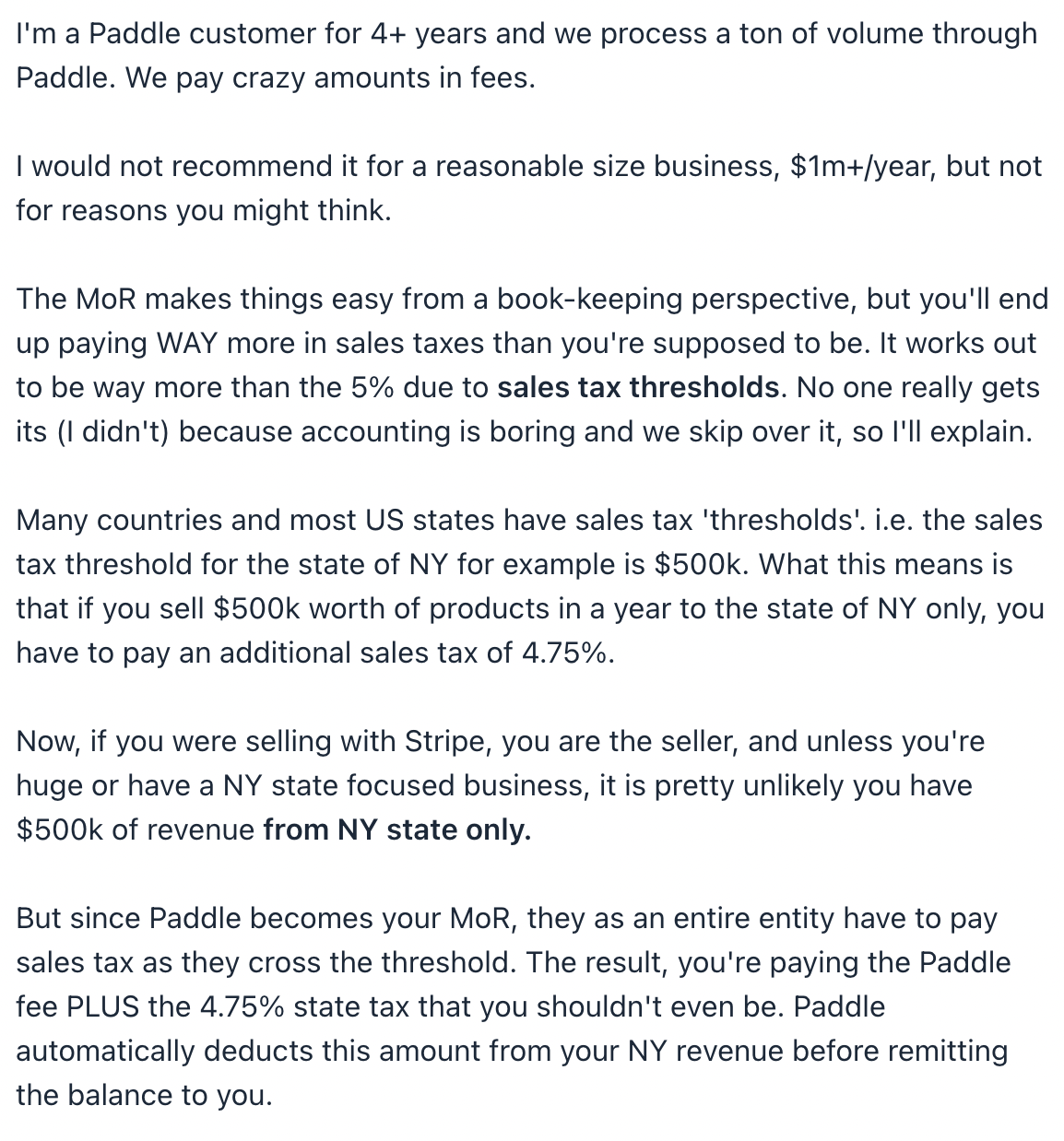

Beyond that, many places charge additional sales tax if you process over a certain amount of payments in a particular geography. For example, New York state charges an additional 4.75% in sales tax if you sell over $500,000 of products in New York.

If you act as your own merchant of record, it would be highly unlikely that you’re over this threshold unless you are running a pretty sizable company. But if you’re using a merchant of record, they are likely over these tax thresholds in every geography.

If you use a merchant or record, you’ll end up paying the highest possible tax rates nearly everywhere in the world.

Here’s a SaaS CEO relaying this:

The point in all of this is that 5% becomes a 7%-14% fee very quickly in a lot of instances. It all depends on where and what you’re selling, but with a MoR you’re almost definitely paying the highest possible rates. The vast majority of SaaS CEO’s that I talked to who are above $1M in annual revenue and using a MoR expressed the same desire to eventually move away from the MoR.

In my opinion, paying 7%-14% of your revenue towards transaction fees in perpetuity is just not a viable long term solution. Paying 7%-14% of your revenue for any single line item is kind of wild if you think about it objectively.

Pros and Cons of Being Your Own Merchant of Record

Pros

Lower payment processing fees

If you act as your own MoR, you have a lot more flexibility when it comes to optimizing for lower payment processing fees. You may very well incur additional costs depending on how you solve for subscription management, tax software, and remittance fees but you give yourself a lot more flexibility to optimize for cost.

For example, you can implement Stripe directly via their APIs so you don’t need to pay for Stripe Billing—that’ll save you .5% to .8% per transaction. You could still elect to use Stripe Tax, which calculates your taxes globally for an additional .5% per transaction.

If you’re in the US, your fees are now at 3.4% per transaction and you’ll have to pay some additional registration and remittance fees for your taxes, but at any sort of scale you’re still a long way from 7%-14% per transaction and you’re not unnecessarily above those revenue thresholds that increase your effective tax rates as you would be with a MoR. It’s just generally cheaper.

As an early stage start-up, this isn’t such a huge deal—but as you begin to scale, optimizing for lower payment processing fees only grows in importance.

Less platform risk—you're responsible for your own business

Being your own merchant of record means you’re in control of your own destiny and are responsible for your own business. This is a huge benefit in my opinion.

Cons

Greater administrative burden

Without question the biggest con to being a merchant of record is that you have to think about this stuff! It’s not handled for you. You need to put tools in place to calculate how much tax you owe and where, and pay to remit taxes in the appropriate jurisdictions.

This represents time away from other work that you could be doing—that’s a major downside in my eyes.

.png)

When to use a MoR—and when not to

What follows is my personal perspective on when using a merchant of record makes sense—and when it doesn’t. Again, every company is different and there’s so much nuance here it’s up to you to evaluate this stuff for yourself. But based on my research and the conversations I’ve had, I think these are some reasonable guidelines to start with.

If you’re a SaaS company that’s just starting out, I would act as my own MoR. In fact, I wouldn’t worry about global sales tax remittance at all (yet).

Queue everyone going bananas, but hear me out. I suggest you start by reading this thread, as it’s representative of my greater point. Almost every successful entrepreneur will tell you the same thing—the world of start-ups is about creating “good problems,” then solving them.

Said another way, there’s no point in preparing for global sales tax remittance before you have a viable business generating significant revenue. If you did every single thing you were told you needed to do before launching a business—to be fully compliant with the laws of every country globally—you’d spend months and tens of thousands of dollars before you even got started on your product. You’d put yourself out of business.

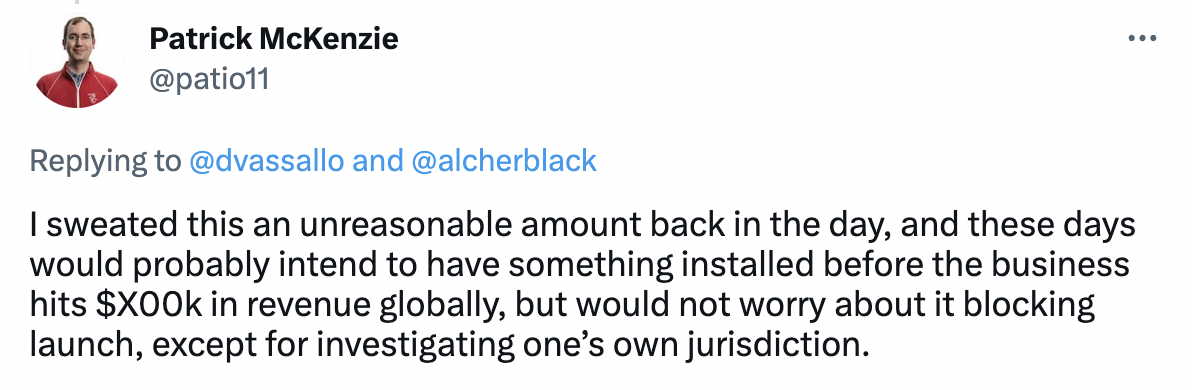

Your job as a start-up founder is to start bringing in money in exchange for your product, and you can absolutely fulfill your obligations once you have a business that warrants doing so. This quote from Patrick Mckenzie tells you everything you need to know—until very recently Patrick worked for Stripe, and he’s generally considered one the pre-eminent experts in all things financially related to operating SaaS businesses. Simply put, he used to obsess over this stuff at an early stage and says he wouldn’t do so anymore.

He is saying, quite directly, that he wouldn’t worry about this stuff until his business is doing hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue.

.png)

In almost 15 years in this industry, I’d estimate less than 5% of SaaS companies under $1M per year in revenue have submitted global sales tax in any way. Go look at your receipts from these companies—I’d betcha almost none of them include sales tax!

In fact, even established companies like Basecamp are just starting to remit global sales tax after making tens of millions of dollars in revenue for years.

If I’m a creator that sells one-time fee digital products, I would recommend using a MoR.

If you’re a creator and you sell one-time products, I think the convenience of using a MoR is simply worth it. You get time back to focus on creating and don’t have to think about the burden that paying taxes represents. And because you’re not selling subscriptions, your fees will be lower. I can live with a 5% fee once—I can't live with a 7%+ fee on an ongoing basis.

If I’m a SaaS company doing over $1M per year I would act as my own MoR.

At some degree of scale, there’s just too much money to be saved by being your own merchant or record.

I think the sensible approach in this scenario is to use Stripe Tax or another of the tax software products to start calculating how much tax you owe and in which geographies. You can then start by remitting tax in your business' home geography, where you have employees, or any geography where you sell a significant volume of software.

The point here is you need to start somewhere, and I think this approach is both feasible and sensible. You start by collecting tax and tracking where you need to remit, and can then remit in jurisdictions where it's sensible to do so over time based on your actual transaction volume. This definitely means that you’re not remitting in every geography, but I think that poses extraordinarily little risk as it is.

Justin Jackson again makes a good point here—even if you are using a merchant of record, the idea that you’ll ever be completely in compliance is a pipedream.

There’s no way—it’s not humanly possible—even for these merchants of record, to be 100%, completely compliant with every tax region in the world at any given moment. The legislation is changing all the time, the rules are changing all the time, and I’ve noticed errors multiple times where merchant of record platforms are making the calculation wrong or their showing the wrong information on the receipt. —Justin Jackson, Co-founder Transistor.fm

With no globally accepted standards around how global sales tax compliance is policed, enforced, or even who is held liable it’s just a non-issue. Using a merchant of record does not represent the safe haven that so many people seem to think it does.

Fear Mongering

I know that I will get plenty of flack for the practical advice that I’ve shared in this article—that’s fine. I’m trying to relay what I’ve found and heard from other founders and CEOs on this topic, as well as my own experiences. Anyone that tells you that you need to remit global sales tax everywhere regardless of your stage or location certainly isn’t wrong, but neither is anyone that’s telling you that you’re safe just because you use a merchant of record.

Higher fees aside, my conclusion is that you expose your business to substantially more risk by using a MoR than by handling global sales tax compliance yourself—even imperfectly.

You also need to think for yourself. Governments globally haven’t figured out how to collect their own taxes themselves… how do you think they’re going to enforce this? The point is not that you should be dodging taxes—I’m advocating for doing everything that’s both sensible and ethical. You should pay remit taxes where you’re located and in geographies where you process a significant volume of payments.

But do you really think that because your start-up sold $39 of software to a customer in Estonia, the Estonian government is going to come knocking on your door? I hate to break it to you, but the Estonian government doesn’t even know your company exists. You can certainly pay that tax to Estonia on day one… but do you really need to?

Keep in mind that anyone that’s selling you anything compliance related is selling based on fear. Derek Sivers—who built a great business himself—has an entire chapter in his book Anything You Want that’s aptly named, “Formalities play on fear. Bravely refuse.”

In reference to a colleague who asked him about the importance of adding things like a privacy policy or terms and conditions to his website, he writes:

“As your business grows, never let the leeches sucker you into all that stuff they pretend you need. They’ll play on your fears, saying that you need this stuff to protect yourself against lawsuits. They’ll scare you into horrible worst-case scenarios. But those are just sales tactics.”

It’s not to say that there’s no benefit in having these things—it’s to say that there’s a time and place when the need for some compliance related items becomes real. Whether someone’s selling you tax software or SOC2 compliance, they’re preying and selling on the fear of what could happen.

Another CEO that I chatted with recently sold his US based SaaS start-up to a publicly traded company for over $500M. The company scaled tens of millions of dollars in revenue and operated for over a decade, never once paying any global sales tax. During due diligence, they simply disclosed that the company had not paid global sales tax as a potential liability. And guess what? It didn’t delay the acquisition for a minute. In fact, the response from the publicly traded acquiring company was “We would have been surprised if you had paid global sales tax.”

Again… fear mongering. This is a common concern that I've heard voiced many times as a reason to use a MoR, but it's very much like hearing about kids eating razor blades in their Halloween candy. A common concern almost never realized.

I want to use a third party Merchant of Record—what do I do?

I’d recommend signing up for Paddle or Lemon Squeezy.

I want to be my own Merchant of Record—what do I do?

- Turn on Stripe Tax or another product that starts collecting taxes for you once you reach what you deem to be appropriate scale. These tools handle tax calculation for you and will tell you what geographies you need to remit in.

- Register to pay taxes in your home geography.

- If you sell to customers in Europe, get a VAT number. If you're based in the US, you can choose any European member state to host your tax registration—choose one with a common language.

- You’ll need to submit one tax payment for all of Europe each quarter. You can do so via an online portal. All the information required is made available by tools like Stripe Tax.

- Here are the remittance partners that Stripe recommends.

The team at Quaderno also offers great guides on how to file and remit taxes online.

Key Takeaways

On this page

Get our newsletter